A newly discovered 14th-century manuscript has cast new doubt on the authenticity of the Shroud of Turin, the linen cloth believed by many to have wrapped the body of Jesus after his crucifixion.

Published in the Journal of Medieval History, the findings reveal that Nicole Oresme, a respected Norman theologian and later Bishop of Lisieux, dismissed the Shroud as a deliberate forgery. In a treatise dated between 1355 and 1382, Oresme identified the cloth—kept in Lirey, France—as an example of religious fraud used by clergy to draw offerings from worshipers.

Dr. Nicolas Sarzeaud, lead author of the study and a historian at the Université Catholique of Louvain, says the document is now the earliest known written rejection of the relic. The manuscript predates the more familiar 1389 memorandum by the Bishop of Troyes, Pierre d’Arcis, who also accused the Shroud’s promoters of deception.

Scientific and historical context

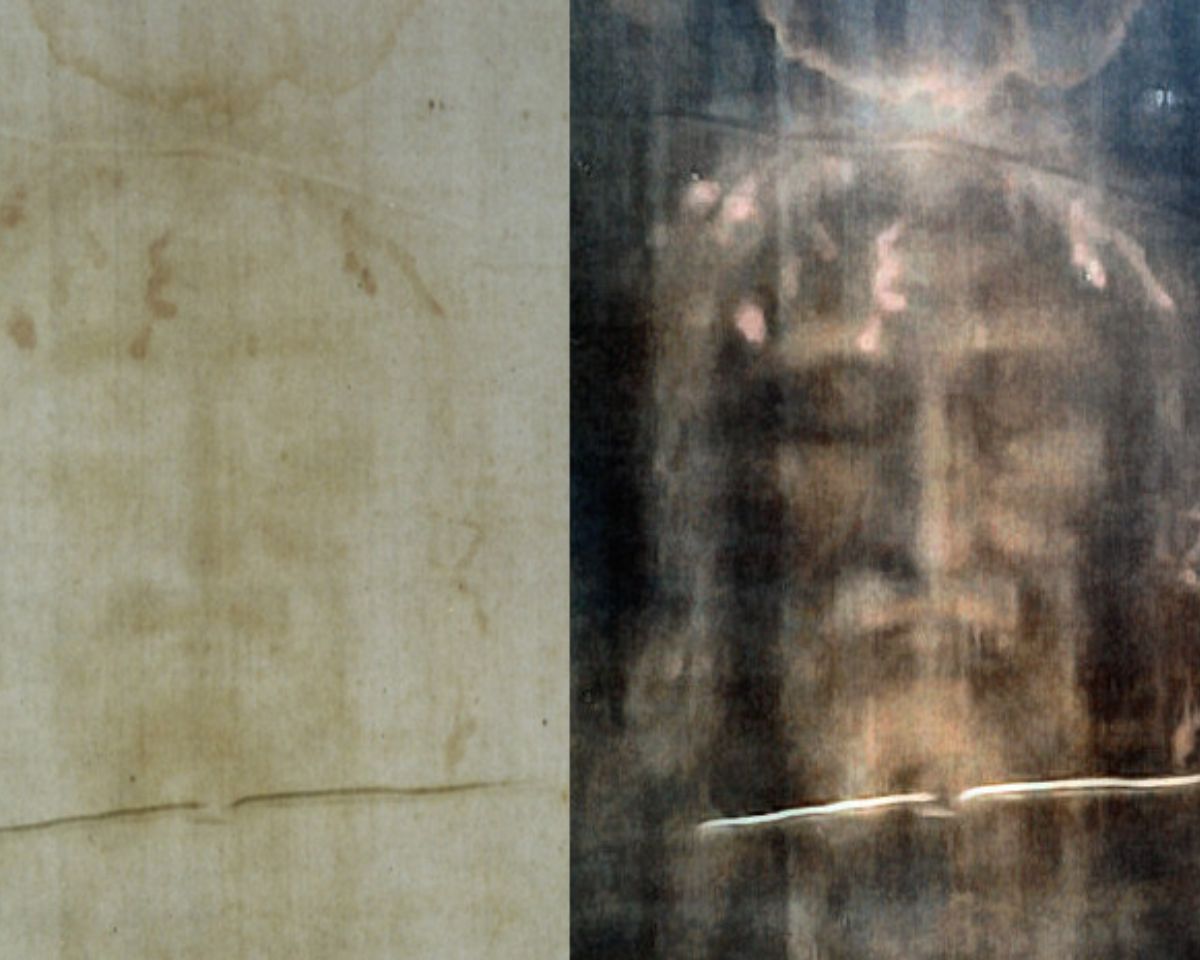

The Shroud of Turin bears a faint image of a naked man, matching traditional depictions of Jesus after his death. However, its authenticity has been questioned for centuries. A 2024 study in Archaeometry used 3D analysis to argue the cloth had been wrapped around a sculpture, not a human body. Earlier radiocarbon testing also dated the linen to the late 13th or early 14th century.

Sarzeaud explains that Oresme’s rejection holds special weight because he was not involved in any disputes over the relic. He was known for applying logic and reason to spiritual claims, often challenging miracle testimonies and weighing the credibility of witnesses.

Oresme specifically referenced the Lirey shrine, saying clergy had falsely claimed the cloth was the burial shroud of Jesus. Sarzeaud adds that this was an unusually direct accusation of fraud, offering rare documentation of religious manipulation in the Middle Ages.

Modern relevance and enduring debate

Professor Andrea Nicolotti, a historian at the University of Turin and expert on the Shroud of Turin, says Oresme’s stance adds historical credibility to skepticism. He notes the case was widely known in the 14th century and even reached audiences in Paris, allowing Oresme to mention it without explanation.

After its removal in 1355 following investigation, the cloth was reapproved for display by Pope Clement VII—but only as a symbolic representation, not a genuine relic. In 1389, it was formally denounced in a Church memorandum as an artificially crafted image.

Sarzeaud believes Oresme’s findings reflect an important moment in medieval critical thought, where even religious figures challenged false claims. Despite the Church’s rejection centuries ago, replicas of the Shroud continue to draw attention worldwide.